Last Updated on 06/11/2023 by AIR OPERATIONS

We meant to issue our 2023 defense markets outlook today but the news coming from the Pacific Northwest is, well, rather interesting. AIR has often previously argued that Boeing has a serious production capacity issue (AIR127) and critically needs to catch up with Airbus and eventually COMAC. There lies the rationale for a 4th 737 MAX FAL. With Renton unable to accommodate a 5th line onsite (we consider the P-8A line to be the 4th 737 line) and Airbus continuing to gradually increase the production rate of its A320 family, Boeing was faced with two options:

- Optimize and work on getting Renton back up to speed as soon as achievable, bearing in mind that Renton remains chronically short-staffed and is exposed to further supply chain bottlenecks with the introduction of two additional variants of the aircraft, the -10 and the -7 from late 2024/2023 respectively. Additionally, space constraints would likely continue to play a role in Renton’s questionable ability to ramp up towards rate 63 (if ever).

- Move part of the production to Everett to ensure that deliveries to key customers such as Ryanair and United are not unnecessarily delayed by Renton’s tight box, supplier disruptions and space related constraints when rates finally get back above 17 for the 3 MAX lines.

There is no third option – moving the 737 out to Moses Lake was not reasonable at such a late stage of the program.

Our negative assessment:

This strategy is grounded in BCA’s production systems ‘inefficiencies, is fraught with risk, and is also symptomatic of the idiosyncrasies of the Puget Sound cluster.

Boeing is operating in a cluster whose characteristics have considerably changed over the past two decades. Skills mismatch are increasingly prevalent in many areas, with salaries unable to cope with one of the highest cost of living in the United States. With commuters facing up to 2 hour drive to travel between the Renton and the Everett locations, the workforce is definitely not as mobile as the distances may suggest. BCA has been finding it increasingly complicated to attract and retain labor for the 737 final assembly line. It takes 6 months to train a machinist and one third of these new hires will be gone after less than a three years ‘stint at Boeing.

Furthermore, most of the machinists working in Renton reside in South Seattle/Kent Valley, whereas those working in Everett are likely to live in the Everett/Marysville area. If Boeing were to ask Renton employees to work in Everett, this would imply a 50 miles drive during peak travel hours with fuel prices well above $5. The migration of part of the Renton workforce simply is not practical and would be logistically challenging for many.

Finally, we also believe that Boeing is unlikely to implement a moving production line identical to the ones in Renton. Our position is based on the monthly rates that we can expect from FAL5 (North Line) in PAE and that are unlikely to exceed 12/month.

Our positive assessment

There was no option for Boeing but to get Everett to pitch in. The 40-26 bay is more than adequate, the rail lines should support the MAX10 fuselage up the hill and, because of the fine print contained in the agreement with IAM, there was nowhere else for BCA to go. The departing 747 and the 737 are of a similar generation, both 50 year old designs and the production system will be familiar for the trainable Everett employees.

That workforce is available, experienced and can be ready to churn MAX10 and MAX8200 by the end of 2024/early 2025. This is the last shot that Boeing has to minimize its growing market share losses to Airbus. However, even if the four MAX lines are able to achieve optimum rates, we expect Boeing to flirt with 65-69 aircraft per month at peak production in a best case scenario; we even question that rationale to a degree. While there is a definite need to catch up with Airbus, such a surge could dry up the backlog too fast. We indeed had anticipated that Boeing would be able to comfortably stretch its production until 2032 based on our revised upwards expected production rates published in November 2022. With Everett now pitching in, that backlog (based on additional expected orders) could be gone by 2030. Although there are a fair amount of Ryanair and Southwest 737NGs that will need replacing, we however do not expect more than 1,100 to 1,500 additional MAX order this decade. This could also suggest that Boeing is looking to increase FCF aggressively ahead of a possible launch of NMA v2 by 2024.

Everett will greatly support Boeing customer’s visibility and delivery timing guarantees. It will also permit BCA to more aggressively compete on price with Airbus during the last decade of the 737 family production. In all, this is a sensible decision, the best according to the circumstances and certainly one that can provide some significant damage control and remediation.

Conclusion: no room for error, but industrial missteps are unlikely. The supply chain remains the 737 Achilles heel.

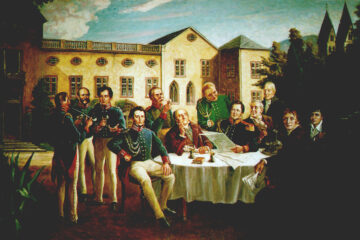

One final military analogy if we may. This is a positive and, with the benefit of Captain Hindsight, an eminently logical move. However, it feels a little bit like the Battle of Eylau (Poland) in 1807. For most of you, this may not ring a bell. Eylau was won by Napoleon’s armies, but at a significant cost. The French leader had to order his best troops (the Old Guard) to bayonet charge in order to save the day, so scant his resources were and with Russian forces having nearly completely eliminated the French center. The Old Guard and a well timed cavalry charge saved the day. It does feel a bit like that with the Everett FAL: commit all resources available, otherwise prepare to lose more.